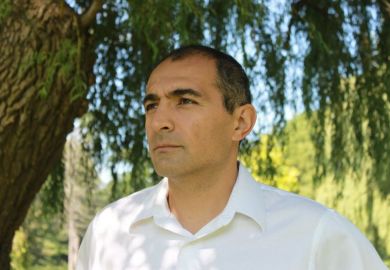

James Morton Turner is professor of environmental studies at Wellesley College. His most recent book, Charged: A History of Batteries and Lessons for a Clean Energy Future, was one of three finalists for this year’s Cundill History Prize, which offers the largest cash prize of any award for non-fiction in English. The book looks at how solving the battery problem is crucial to a clean energy transition and at the question of whether the environmental impact of batteries – including the mining of materials to make them – means that transition could risk trading one set of problems for another.

Where were you born?

Roanoke, Virginia, a small town in the Blue Ridge Mountains.

How has this shaped you?

Growing up in the Blue Ridge Mountains kindled my interest in nature and the environment. When I realised those mountains, which I had always thought of as timeless, had a history, I started on the long path towards becoming an environmental historian.

What’s the role of an environmental historian – as distinct from that of a climate scientist – in spreading understanding about climate change and the energy transition?

At this point, the obstacles to addressing climate change have less to do with our understanding of climate science and much more to do with the economic, social and political obstacles to remaking our societies and our energy systems in ways that are consistent with stabilising the global climate. Addressing those challenges means delving into issues of ethics, culture and even identity – topics about which a wide range of scholars have much to offer. My work as an environmental historian, specifically, is focused on how better understanding the consequences of building energy systems of the past can help us plan ahead for the social, ethical and material consequences of building a new, clean energy system for the 21st century. It isn’t enough to phase out fossil fuels; we have to simultaneously find ways to phase in renewable energy systems that are both sustainable and just.

What can the history of batteries tell us about our energy future?

In most studies of energy history, batteries are a footnote at best. But batteries have always been what I describe as an enabling technology, playing a little appreciated but critical role in enabling larger energy systems. For instance, the starter battery had a lot to do with the success of the conventional gasoline-powered automobile. Understanding the history of batteries can help us reckon with the extraordinary demand for materials needed to support a clean energy transition. As we transition away from fossil fuels to clean energy systems, the role of batteries as an enabling technology is going to become even more important.

You made the point in your recent New York Times essay that China was largely a bystander in the petroleum energy age, but won’t be in the clean energy transition. What power does China have on batteries, and what might that mean for the West?

China started investing in batteries because it saw an opportunity to strengthen its role in consumer electronics manufacturing in the early 2000s. Those early investments gave China a significant head start in developing the manufacturing capacity and supply chains needed to support the production of advanced batteries, which it has now scaled to electrify automobiles and support renewables on the electric grid. As a result, China plays an outsize role in the entire lithium-ion battery supply chain, processing the vast majority of materials needed for lithium-ion batteries and dominating the production of those batteries. That has geopolitical implications. As the materials needed for energy systems shift from fossil fuels to critical minerals, that will mean a growing dependency on China, unless supply chains are diversified.

Have you been looking to get traction with politicians and policymakers working on clean energy?

Two years ago, as I finished my book Charged, what had been a trickle of battery-related announcements in the US became a flood. Working with students at Wellesley College, I started tracking those announcements systematically. At first, the idea was that the tracking would be an excuse to put out monthly updates and, at the same time, remind people that I had written a book on a related topic. But things changed with the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022. The climate and energy law includes numerous incentives for onshoring the battery industry to the United States. When that law passed, my students and I were sitting on a database of domestic electric vehicle investments, which we’ve continued to update as the announcements have accelerated. Between our tracking and the policy recommendations in Charged, I’ve found myself involved in conversations with a range of policymakers, industry executives and non-governmental organisations.

Wellesley has a distinctive position as a women’s college. What’s it like working there?

Wellesley is an amazing place to be a teacher and a researcher. The students are motivated, deeply concerned about environmental justice issues, and often interested in careers in public service. The inspiration for Charged came from teaching my introductory course on climate change, where students already had basic understandings of many energy systems – but for them, like me, batteries were a black box. I wouldn’t have completed Charged without their assistance. Students helped with the research, the fact-checking and, most recently, the tracking work we’ve been doing.

Is there a book that changed how you look at the world?

William Cronon’s Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West turned my world upside down. It shattered the ideas I had about the history of the environment, the relationship between the economy and ecology, and what we see and don’t see in cities and nature.

When are you happiest?

As much as I love teaching and being a scholar, I also have a passion for carpentry projects. There is something deeply satisfying about building an extension and having everything come out true.

john.morgan@timeshighereducation.com

CV

1995 bachelor of science, Washington and Lee University

1996 master of arts, American civilisation, Brown University

2004 PhD, history of science, Princeton University

2006-present assistant professor and professor in environmental studies, Wellesley College

2012 The Promise of Wilderness: American Environmental Politics since 1964

2018 The Great Reversal: Conservatives and the Environment from Nixon to Trump (co-author)

2022 Charged: A History of Batteries and Lessons for a Clean Energy Future

Appointments

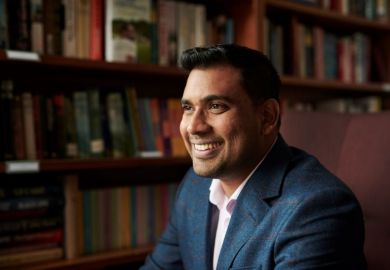

Rachel Langford will be the next vice-chancellor of Cardiff Metropolitan University. She will replace Cara Aitchison on her retirement in February, in a promotion from her current post as deputy vice-chancellor. The appointment was announced after Helen Langton, who was due to join Cardiff Met as vice-chancellor from the University of Suffolk, withdrew for personal reasons. Professor Langford, who previously held senior roles at Oxford Brookes and Cardiff universities, said she was “looking forward to continuing to work with colleagues to deliver the university’s ambitious strategic plans for the future”.

Jo Angouri has been appointed deputy pro vice-chancellor for education and internationalisation at the University of Warwick. A professor in sociolinguistics at Warwick, Professor Angouri also holds visiting positions at Aalto University, Monash University and Victoria University of Wellington and holds the Lonnoy chair for Multilingualism at Vrije Universiteit Brussel. She said she would work to “ensure that Warwick delivers a sector-leading, excellent student learning journey which is international, interdisciplinary and inclusive”.

Yusra Mouzughi is joining the University of Birmingham Dubai as its next provost, replacing David Sadler. Currently president of the Royal University for Women in Bahrain, Professor Mouzughi previously spent five years at Muscat University in Oman, first as deputy vice-chancellor for academic affairs and then as the institution’s first female vice-chancellor.

Paul Kittle has been named vice-chancellor for student affairs for the University of Houston System and vice-president for student affairs for the University of Houston. He moves from the University of Texas at Arlington, where he has been senior associate vice-president for student affairs.

Rajani Naidoo has been appointed deputy vice-chancellor for people and culture at the University of Exeter. She is currently vice-president for community and inclusion at the University of Bath.

Harriet Dunbar-Morris is joining the University of Buckingham as pro vice-chancellor, academic. She moves from the University of Portsmouth, where she has served as dean for learning and teaching.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login