“Publish on Amazon and be damned” is something that the Duke of Wellington might well have said, had he been born two centuries later. To some, this new, relatively unfiltered and uncontrolled form of dissemination may seem little more prestigious than running your own blog. As someone who has published five books with academic presses since 2007, I am now about to publish my sixth, A Century of Supernatural Stories, on Kindle, and via CreateSpace, as a print-on-demand paperback.

Why? The first and simplest answer is: because I want a lot of people to read it. The book is a collection of supernatural tales from 19th-century newspapers, with explanation and commentary derived from my research on magic, witchcraft, vampires, ghosts and poltergeists. Published in their original prose, the tales seem to me to have a nicely textured voice of the period, but they are often also pretty compelling in their own right. I can vouch for this as I’ve got into the habit of paraphrasing them for all sorts of patient listeners over the past few months, most of whom were neither students nor academics.

I am probably not alone in buying a book “on spec” after a quick glance in a bookshop. But while I would readily do this with a paperback priced under £10, I would hesitate with something costing three times that. Century is due to retail at around £8, whereas the paperback edition of one of my existing books is going to cost slightly more than £30. This is, admittedly, a long book; but the only interest I had from an academic publisher for Century was as part of a series for schools, which would have seen a longer version of it retailing at £100.

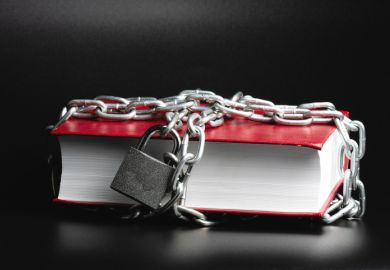

Those inside the trade publishing world will tell you that, nowadays, it is very hard to sell non-fiction unless you have television tie-in or a “difficult lives” story. Self-publishing is a way to test this claim. It also allows you to disseminate research quickly. In the present case this is very important. Century is devoted to ghost and poltergeist experiences that are very difficult to swallow on first contact. They defy the laws of physics, and they violate the accepted worldviews of many rationalists. But there is very good reason to take them seriously. They have been reported by a strikingly wide range of witnesses, including lawyers, police officers, journalists, scientists and academics. Moreover, it is only once you get into the habit of talking about this subject that people you have known for years will suddenly say: “Yes – that’s happened to me.” By putting these stories out there, and comparing them with more recent cases, I aim to raise the profile of what is currently still a marginal, if not taboo, subject. To me, this is one of the most important things that universities do: they raise difficult questions.

More practically, I also want to encourage people to share their own supernatural experiences with me. One of the many strange things about this topic is that, two decades into the internet age, so much interesting material still has not been published in any form. What I have learned so far from private discussions has been invaluable to me; and I have also had the sense that those telling the stories have appreciated being able to share them with someone who takes them seriously.

In an era of high tuition fees it is important to let people who cannot afford them have access to my research. At the same time, the impact and public engagement agendas have brought exciting new possibilities; long before the next research excellence framework deadline, I am being asked to write up drafts about my poltergeist research. Meanwhile, many academic presses are only becoming more specialised, and less interested in the intelligent general reader.

But what about peer review? For many areas of research this is invaluable. For ghosts and poltergeists, it is not. A half-hour conversation with someone who has experienced a poltergeist is far more valuable than most of the peer review reports one might get on 100,000 words of text.

To some colleagues, self-publishing is probably vanity publishing. Perhaps it is if you are not able to publish anywhere else. Personally, I expect also to be entering two or three academic books for the REF, just as in past submissions. And if we take “vanity” in that biblical sense of “futility”, then surely giving large numbers of people the chance to read your books is anything but futile.

However, I should add that I am not at all prescriptive about what people might get from Century. If they think, “Dear God, did that really happen in the 19th century?”, then that is the best impact I would ever hope to get. I can and will make a very rigorous case for the historical, psychological and even scientific reach of my research on the supernatural. But this is also an area in which I am lucky enough to be able, simply, to say to a great many people on trains, in swimming pools or at parties: “Look, let me tell you…because this is interesting.”

Richard Sugg is a lecturer in the department of English studies at Durham University.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Step over to the other side

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login