It is widely agreed that this is the “Asian century”. Yet it is easy to point to evidence – escalating trade wars, diplomatic “cold wars”, the misjudging of the initial Covid outbreak and even physical attacks on overseas Asian students and academics – suggesting that Western politicians and citizens have little understanding of Asia and its people. This raises obvious challenges for business, policymaking and diplomacy, where universities might be expected to help bridge the gap. Yet they can provide little help as long as Asia studies remains a minor and marginalised discipline within most institutions.

Experts warn that universities and politicians are doing their nations a disservice by failing to give Asia the attention it merits. One sobering assessment comes from Scott Kennedy, a senior adviser at the Washington-based Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS) and the founding academic director of Indiana University’s China Office: “There has always been insufficient attention paid to Asia in American universities, and probably elsewhere, relative to the significance of Asia.” If things get even worse, “we will learn less and understand less at a time when we need to know more. The gap between what we know and what we need to know will widen.”

THE Campus resource: Tips for engaging Asian universities and alumni in new modes of collaboration

That view is endorsed by Adam Habib, director of SOAS, University of London. “Asia has the largest human population on the planet. We can’t think through the global challenges of our time without thinking through Asia,” he says. “The economic fulcrum of trade is starting to tip towards Asia. If trade over the Pacific develops faster than the Atlantic, the economic fulcrum will tip over. You can’t understand the global economy today without understanding Asia.”

The problem isn’t just that Asia studies is failing to expand as Asia’s geopolitical footprint grows. According to Pardis Madhavi, dean of social sciences at Arizona State University, the subject is actually declining. “We face a triple pandemic,” she says: “a viral pandemic related to global health; a social pandemic of racism; and climate emergencies. We need coordinated efforts that begin with coordinated knowledge to tackle some of the world’s most wicked problems.”

It can be argued that the situation is most serious in the UK, whose ministers have pitched Brexit in part as a conscious effort to pivot from trade with established markets on the nation’s doorstep towards greater interaction with much faster-growing economies further east.

“The study of Asia in Britain is still not given enough emphasis,” suggests Rana Mitter, director of the University of Oxford China Centre. “There are many areas of excellence in terms of teaching and research, but the overall sense that a post-Brexit country needs to understand Asia in a more holistic sense – including its sociologies, political systems and histories, as well as languages – is not yet very sharply felt.”

The gaps in knowledge about Asia’s superpower, China, are particularly keenly felt, Mitter argues. The emergence of Covid-19 is a case in point. He warned as early as spring 2020 that “it’s very important to understand the role of China in the virus crisis and base our assessment on facts, not myths”. He amplified this point in an essay co-written with Elspeth Johnson and published in Harvard Business Review, “What the West Gets Wrong About China”.

“Many in the West,” they argue, “accept the version of China that it has presented to the world” in “English-language promotional materials”, which stresses “the outward-facing, Confucian concepts of ‘benevolence’ and ‘harmony’”. However, the reality is rather more complicated, they say. Furthermore, Western leaders cling to “assumptions [that] reflect gaps in their knowledge about China’s history, culture, and language that encourage them to draw persuasive but deeply flawed analogies between China and other countries” – for example, that China will take the same development track as Western Europe and Japan, or that “authoritarian political systems can’t be legitimate”.

Although China has changed beyond recognition since the 1990s, Mitter and Johnson reflect, “one thing hasn’t changed...Many Western politicians and business executives still don’t get China.” This clearly reflects, among other things, the failures of Western universities to develop and promulgate the knowledge that would enable non-experts to get beyond myths and PR spin.

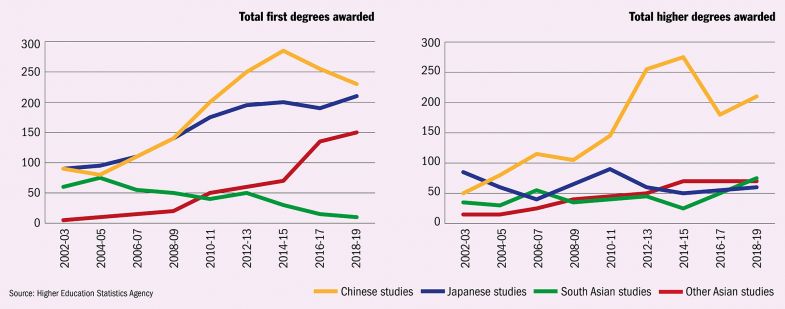

Overview of Asian studies degrees in the UK

Ignorance about Asia’s other major economic player, India, is similarly damaging. As the pandemic has taught us, “when it comes to global health, we are in this together”, says Nathan Grills, a professor at the Melbourne School of Population and Global Health and a senior research adviser at the Australia India Institute. “No man is an island and we need to better understand the health situation and drivers.”

It is a real problem, therefore, that “not enough attention [is] paid to the study of India and South Asia”, where there could be emerging health crises, such as antimicrobial resistance. “In regards to health – emerging diseases, treatments and research,” warns Grills, “we ignore India at our peril.”

Australia represents a partial exception to the generally bleak picture among anglophone countries. According to Edward Aspinall, former president of the Asian Studies Association of Australia (ASAA) and a politics professor at the Australian National University, “the big picture of the past 50 years is that Australia has really punched above its weight in the study of Asia – its politics, history, culture and literature. This is due to our geographic location, economy and cultural orientation.”

This is just as well, he adds, because “we lose out on the opportunity to benefit and grow – not just financially – without deeper understanding of Asia. And scholarly engagement is an entry point for that deeper process.”

As a result, Asia studies in Australia is relatively robust. A 2020 analysis by the ASAA found that China study centres were being opened or expanded at the University of Sydney, the University of Melbourne, La Trobe University and UNSW Sydney. At least before Covid, Chinese-language courses at some of the larger institutions had more than 1,000 students each (although critics have noted that many of these students are themselves Chinese). And Australia is probably the only anglophone country whose HE system has included deep study of Indonesia, its enormous neighbour with 270 million people.

However, Anne McLaren, professor in Chinese studies at the University of Melbourne and the author of the ASAA report, writes that “Australia still has too few Australian China specialists to meet the national need for expert engagement with our largest trading partner.”

Aspinall also worries that “study of security and international relations has not been matched by growth in understanding its society, cultural change and economic transformation” – and indeed that “the deep study of China has not kept pace with the influence of China”.

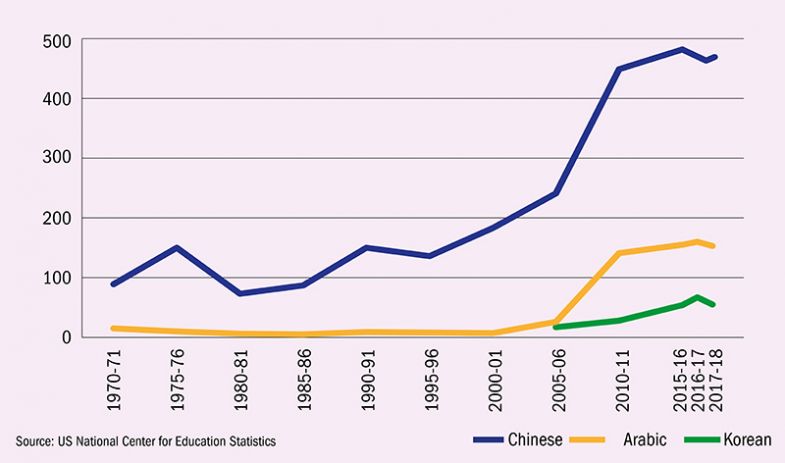

US bachelor’s degrees conferred in language and literature courses

Asia is a continent of 4.5 billion people and about 50 nations and states. As well as the sheer scale of Asia studies in Western universities, some scholars are concerned about emphases in teaching and research that can easily lead to oversimplification or loss of context.

Philippe Peycam, director of the International Institute for Asia Studies (IIAS), based at Leiden University in the Netherlands, says that “Asia studies departments are limited only to certain universities and are largely based on language training. And within that area, most of that is Chinese – especially Mandarin – and Japanese.”

Himself an expert on Southeast Asian nations such as Vietnam and Cambodia, Peycam would also like more account to be taken of this region, which has a population that rivals continental Europe and is sometimes tipped as the world’s next HE powerhouse.

Meanwhile, Arizona State’s Madhavi, who is herself a scholarly authority on Iran, is “constantly frustrated by how much West Asia and Central Asia are overlooked”. She also feels that military conflict and geopolitics play too great a role in research: “Studies of the Middle East tend to focus on conflict – specifically Israel/Palestine – or they tend to be steeped in early 2000s-era ‘War on Terror’ speak. There is so much more to the region, and to Central Asia as well as South Asia.”

There are a number of reasons why the study of Asia is currently at a low ebb.

The most obvious is linguistic. The four hardest languages for English speakers are Arabic, Chinese, Japanese and Korean, according to the World Economic Forum and US Foreign Service Institute. As a result, Mandarin is only the sixth most popular second language taught in the US, after French, American Sign Language, German, Japanese and Italian, according to a 2019 report by the Modern Language Association.

Pradeep Taneja, a senior lecturer in Asian studies at the University of Melbourne, points to another problem when it comes to boosting his discipline in the West, namely that “interest in the study of any Asian country tends to fluctuate with the ups and downs of the economic growth of the country”.

This happened to China studies in the late 1980s, and to Japan studies before that. Interest in India picked up in the mid-2000s, because of the country’s growth. Taneja suspects, however, that “the pandemic-induced economic downturn will regrettably dampen demand for Indian studies in the Anglosphere”.

Such trends are driven, argues Taneja, by “governments in English-speaking countries, [which] tend to prioritise trade and economic opportunities” over broader curiosity about other cultures, and by students who “have concerns about job prospects at the back of their minds”.

Indeed, the IIAS’ Peycam regards “the very narrative of the ‘rise of Asia’” as problematic “because it originates in the West and presumes that Asia is either a new opportunity or new threat”.

But, according to Taneja, any turn away from studying India would be “very short-sighted”, not only because countries’ economic prospects can change but because the nearly 1.4 billion people living in India “will help shape the interconnected world we all live in”.

Research and teaching priorities are also driven by politics. The popularity of Chinese courses rose steadily ahead of the 2008 Beijing Olympics, a friendlier time in Sino-US relations, until 2012, when interest began to fall off. Meanwhile, fewer American students were taking language classes in China, even before the country closed its doors to most foreign students starting in early 2020. Negative news stories about the country may be turning off both administrators and students. And “US-China tensions”, as CSIS’ Kennedy explains, add to the practical challenges, since they “have overturned hopes for direct interaction – meaning study abroad, offices on the ground, transaction exchanges, even alumni outreach”. Detentions in China have also put off dedicated Sinologists from travel.

Another problem has been the marginalisation of Confucius Institutes, the hundreds of Mandarin-language schools that the Chinese government opened across the world. While these are well funded, they are also accused of interfering with academic freedom on the foreign campuses where they are embedded. Nearly half of those in the US closed during Donald Trump’s term of office. Jitters about the institutes were also felt in Europe. In July, Germany said that they have been “given too much space” – although it also pledged an additional €5 million (£4.3 million) to bolster its own “independent China expertise”.

Meanwhile, other Asian states are making efforts to boost their own languages overseas. In June, South Korea announced that it would grow the number of overseas Korean-language schools it funds, known as King Sejong Institutes, from 234 to 270 by the end of 2022, local media reported. Korean-language studies are already on the rise overseas, owing to the prominence of K-pop music and movies. This “soft power” phenomenon already has a name in Asian academic circles: Hallyu studies.

Yet it is clearly dysfunctional for student numbers and levels of research to be so influenced by whether a particular Asian nation is seen in a positive or negative light at a particular moment. Either way, “you need to know potential friends and enemies,” as Kennedy points out: “how they work, their intentions and motivations.”

So where might we turn for signs of hope about the future of Asia studies?

There are some examples of academics and students pushing back against proposals to cut back certain programmes. In May, Stanford University reversed a decision to close its Cantonese-language offerings, which it had previously said would be a victim of $100 million (£73 million) budget cuts in the 2020-21 school year. This seems to have been partly in response to a lobbying group called Save Cantonese, which was formed to ensure the survival of courses in the language (spoken by an estimated 60 million people, including in Hong Kong, southern China and large parts of the Chinese diaspora).

More significantly, institutional leaders and others are actively looking at ways to rethink what “Asia studies” might mean.

While IIAS is based at a university, Peycam says that its goal is to operate in a different and more collaborative way than a traditional university department.

“We don’t want to create yet another ‘Asian studies centre’,” he explains. “We want vibrant platforms that support the facilitation of intellectual collaboration across Asia in a broad sense.”

For example, IIAS hosts the secretariat of the Urban Knowledge Network Asia, which includes 120 urban studies researchers and cooperates with NGOs, community groups and local governments in Asia.

“We want to go beyond a Cold War, colonial mentality of Western experts commenting on Asia, as opposed to being in Asia and with Asia,” he says. “But it is difficult for Western academic institutions to think beyond their traditional patterns.”

Aarti Kawlra, the academic director of an IIAS programme called Humanities across Borders: Asia & Africa in the World, takes a similar line. Regretting the “shrinking space for the humanities” across all disciplines, she urges institutions to “go beyond just international relations – that’s a bit 20th century. We need to look at global contexts and de-nationalise. In the 21st century, we need to look at the new realities of how Asian people live.”

More concretely, Kawlra would like to see universities offering “foundational studies” that incorporate the global South, including Asia, into broader curricula.

“If you’re a student in STEM or business and you want to go out into the world to work, you need to have an idea of historic, cultural and geographical realities,” she argues.

Habib, who took over at SOAS earlier this year after leading the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa, already sees changes in the way Western academics engage with Asia and other areas of the developing world. “Asia was once an area that we studied – but today it is an area in which we partner with institutions to interrogate and address the planetary questions of our time. Asia is less ‘the other’ that we study and more a part of who we are,” he says.

But the ability of SOAS – one of the world’s pre-eminent institutions studying Asia – to pursue such partnerships is hampered by the financial difficulties it has recently faced. More resources would “enable us to do more to address the planetary questions of our time from the perspective of our focus regions, and from the perspective of marginalised communities in Asia”, Habib reflects.

There are many eloquent voices pointing to the need for new forms of Asia studies, based on a wider and deeper understanding of the continent’s peoples and a commitment to true partnerships to address global problems. It remains to be seen, however, whether they will enable Western universities to bridge Kennedy’s gap between “what we know and what we need to know”.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login