Equitable teaching that creates pathways to success for all students

Andrew Estrada Phuong and co-authors present a framework for an adaptive equity-oriented pedagogy that helps diverse students achieve better results

You may also like

Popular resources

When creating pathways for student success, particularly for under-represented students, it is important to understand their perspectives, strengths, histories and barriers to learning. Collecting this information and feedback enables educators to understand students holistically.

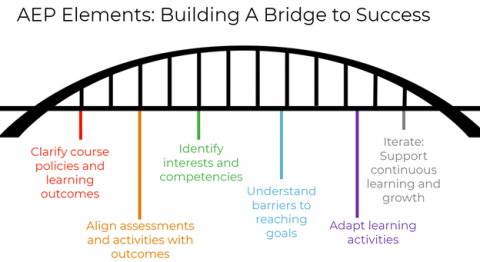

An adaptive equity-oriented pedagogy that boosts student success

We designed an adaptive equity-oriented pedagogy (AEP) framework that increased student achievement by more than a letter grade. Our experience in faculty and graduate student development shows that equipping instructors with adaptive equity-oriented pedagogy strategies improves their teaching and prepares them to meet the needs of diverse students by:

-

Clarifying learning outcomes

-

Aligning formative assessments with outcomes

-

Identifying students’ competencies, interests and needs

-

Understanding equity barriers to meeting outcomes

-

Adapting teaching practices based on these needs and barriers

-

Iterating: reflecting upon pedagogy to support continuous learning and growth

Here, we share ways that instructors can integrate elements of adaptive equity-oriented pedagogy in their classrooms. We’ll starting by looking at how to understand student needs.

One way is for instructors to assign a journal entry task that includes questions students answer online for participation credit at the beginning of the semester.

-

Why did you take this course? How is this course relevant to your interests?

-

What concepts do you anticipate being the most challenging to learn in this course?

-

What things have teachers done, both in high school and in college, that have hindered your learning?

-

Reflect on your best teachers. What teaching practices have been the most impactful on your learning?

-

What factors, if any, outside the classroom impact your success inside the classroom? Please discuss only what you feel comfortable sharing.

After collecting this information, instructors should look at the most frequent kinds of responses, especially those that help them understand what they see in assessment data, for example, patterns in student performance, student feedback, classroom observations. Consider adjusting teaching methods when a theme is noted by more than 10 per cent of the class.

For issues identified by less than 10 per cent of students, think about what individualised support and targeted resources could be provided, such as video recordings of class, specific readings and supplemental resources that do not assume prior knowledge.

Questions two to five listed above can help instructors develop community norms where students identify teaching practices that either hindered or promoted their learning. The goal is to make the learning environment welcoming, supportive and challenging. Clearly articulated classroom norms can create community agreements that foster a brave and inclusive space for critical engagement, continuous learning and growth.

Responses to question five are key because they offer instructors a chance to identify barriers to learning. When identifying barriers to equity, many students may point to factors outside the classroom as well as impostor syndrome, or stereotype threat – a stereotype about one’s identity that negatively impacts behaviour and learning. The strategies below promote success for all students, including those who may view their identities and levels of prior preparation and knowledge as disadvantages.

These adaptive equity-oriented pedagogy strategies include:

1) Modelling expert thinking by showing how you expect students to approach a problem or task with written step-by-step instructions. This helps students identify the skills and thought processes to apply when completing various assessments and tasks, which builds confidence.

2) Providing opportunities to deliberately practise expert thinking strategies individually and in small groups with ongoing, low-stakes feedback.

3) Providing strategies for students to use their time effectively outside class and indicators as to when students should ask for help. For example, you can write or say: “If you’re spending more than three hours on this assignment, come to office hours or send us an email. We’re committed to your success!”

4) Normalising an environment where growth is highly valued like content expertise. This involves fostering a brave space where students are encouraged to seek support and feel able to openly express when they do not know or feel unclear about something.

5) Offering flexibility, such as deadline extensions, and being supportive when students experience contextual challenges such as internet access issues, lack of a study space at home, and basic needs access.

6) Validating students’ classroom contributions that promote learning.

7) Encouraging students to affirm each others’ contributions in class or via a discussion board.

8) Providing assignments, such as projects, homework and videos, where students can apply concepts that are relevant to their lived experiences, interests and career goals. This is an opportunity for students to bring themselves into the curricula, applying concepts to novel contexts that are meaningful.

In our research, students reported that adaptive equity-oriented pedagogy strategies and ongoing validation helped them recognise that their success was not predetermined by their identities or background, but rather through their effort and engagement with course material.

The strategies reduced barriers to equity, showing that clear expectations, problem-solving strategies, ongoing feedback and meaningful projects advanced students’ success, student data revealed.

How can instructors get helpful feedback from students?

During the semester, ask students to respond anonymously to the following question:

-

If you were to teach this class, what is one specific practice that you would do differently or include to further your learning in ways that align with course goals? Why?

This question allows students to feel more comfortable and brave when providing feedback as suggestions are additional ideas for instructors to consider. Student responses do not denigrate the instructor, but rather provide additional ideas for instructors to consider.

What if there’s conflicting feedback from students?

We recommend that instructors make student data and instructional decisions transparent, especially when there is conflicting anonymous feedback from students.

For example, if it were the case, it might be effective to let students know if there are about a third of students who prefer lecture, another third who prefers discussion, and another third who prefers activities. In line with the universal design for learning, this approach enables instructors to discuss and reinforce material through varying formats – lecture, discussion and activities – to target all students’ preferred modes of learning at different times during class.

Making student data transparent and diversifying instructional approaches to include all these mediums can bolster engagement and a sense of community and belonging. It sends a message to students that they have a voice and their feedback is valued in transforming pedagogy.

Making the learning environment more equitable improves the experience for students and instructors alike. Adaptive equity-oriented pedagogy practices can achieve this goal for in-person and online courses.

Andrew Estrada Phuong is a Chancellor’s Fellow, consultant and programme developer; Fabrizio Mejia is assistant vice-chancellor for student equity and success; and Christopher Hunn is a lecturer in computer science – all at the University of California, Berkeley.

Judy Nguyen is a PhD student in the developmental and psychological sciences programme at Stanford University.

Dena Marie is PhD candidate in Hispanic languages and literature at the University of California, Berkeley and a Spanish teacher at the Orinda Academy.

Additional Links

A 2017 paper by Andrew Estrada Phuong, Judy Nguyen and Dena Marie, “Evaluating an Adaptive Equity-Oriented Pedagogy: A Study of its Impacts in Higher Education”

Further guidance on strategies for soliciting more effective student feedback, from the University of Michigan’s Center for Research Learning and Teaching.