You can judge a book by its cover – at least in this case. Rhodri Lewis’ sombre dust jacket reproduces some of the more gory sections of A Hunting Scene, painted by Piero di Cosimo about a century before the first performances of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Lewis describes the image: “an all but feral community of appetitive violence, with human beings competing against one another and the animals on whom they preyed”. Hamlet and the Vision of Darkness reads Shakespeare’s tragedy as a defiant rejection of the humanist aspirations of the early moderns: “while humanist educators stuck to their pious ideology in championing the light of self-knowledge, for the Shakespeare of Hamlet, humankind is bound in ignorance of itself”.

Lewis’ critical method is thorough and systematic. He cites chapter and verse of the various “auctoritees”, authors of humanistic treatises on history, poetics, philosophy and hunting. With

diligence and patience, he traces these back to their classical sources. Then he shows how poorly Hamlet acts upon, articulates or personifies their principles. At points, this amounts to little more than character assassination: “Hamlet emerges as a thinker of unrelenting superficiality, confusion, and pious self-deceit” or “the thoughts to which he gives voice are the ill-arranged and ill-digested harvest of his bookish education”. Occasionally, the attacks are cheap shots: “Prince Hamlet is the inhabitant of Elsinore most thoroughly mired in bullshit” or, in a throwaway description of the Prince’s “If it be now, ’tis not to come; if it be not to come it will be now…” speech, Lewis remarks that he utters “pseudo-profundities worthy of Yoda”.

It is as though English drama’s most exciting hero is, for Lewis, flat, stale and unprofitable. Furthermore, in Lewis’ opinion, Shakespeare also disapproved of his own most complex and fascinating dramatic creation. Hamlet, Lewis argues, is a personification of all that is wrong with humanism’s conventional wisdoms – poetic, historical and philosophical. Why Shakespeare would go to the trouble of personifying his refutation of humanism is not explained; why he would do so in a play is even more mystifying. Might an audience, Elizabethan or modern, have the slightest idea that the plight of Renaissance drama’s greatest protagonist is nothing more than a caricature of the wisdom of the ancients?

Too often, Lewis’ trouncing of Hamlet originates with an ingenious but hair-splitting point. For instance, apropos Hamlet’s “There’s a special providence in the fall of a sparrow”, Lewis discusses the clash between Roman augury and biblical parables (with reference to the sparrows of Matthew x, 29-31). If, Lewis rightly maintains, Hamlet defies augury, he is defying “something that does not exist, and Christian providence makes it quite plain that the divinatory claims of pagan religion are an idolatrous sham. Either the Christian or the Roman view of the matter may be right; both views, likewise, might be wrong. But…they cannot both be right.” Fair enough, but Lewis lays into Hamlet as though this contradiction betrays the fact that the prince himself, and the humanist view he apparently represents, is some kind of fraud: “Habituated in the techniques of rhetorical bricolage, Hamlet will say anything that springs to mind, irrespective of its logical incoherence or indifference to truth.”

But Hamlet is a fictional character and isn’t it just as likely that the playwright is making him plausible in the eyes of his audience? Aren’t characters (fictional as well as factual) contradictory or untruthful from time to time? One might as well argue that Bottom is flawed because human beings don’t turn into donkeys. A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Hamlet are plays, not zoological handbooks or humanist tracts. Lewis, however, remains aggrieved that Hamlet is “untroubled by his failure to make any sort of sense”, as though logical consistency trumps theatrical plausibility. (What a good job Lewis isn’t writing about Samuel Beckett!)

The problem is that Lewis writes about a play – a work of dramatic fiction – as though it were a sustained critique of an intellectual position and only that. Indeed, Hamlet’s alleged disdain for the theatre is something Lewis attacks: “[Hamlet] is uninterested in either the form or content of the plays he admires. Uninterested in the way they have been written…Uninterested in staging, casting, or the dynamics of an acting company. Uninterested in the opinions of audience members who do not agree with him.” Never mind that Hamlet writes new speeches for the players; never mind that he gives them notes regarding gesture or volume in the manner of a modern director, never mind that he defends their reputation in front of the censorious Polonius. It is neither Hamlet nor Shakespeare who is uninterested in theatre; it is Lewis.

Shakespeare studies is a broad church, but the centrality of the play itself is the governing principle. Critics such as Michael Dobson, Andrew Gurr, Peter Holland, Jean E. Howard, Lois Potter, Tiffany Stern and Stanley Wells have shown us how the theatrical intercourse between actor and audience is an ineluctable part of our understanding of Shakespeare’s art. They are theatre historians, textual scholars, analysts of theatrical reception, historians of patronage and censorship, but there is no way round their prioritisation of the plays’ theatrical essence.

New historicist Shakespeareans (Stephen Greenblatt, Katharine Maus, Louis Adrian Montrose) are interested in the ways that the plays establish and promulgate the inequitable distribution of power in Elizabethan and Jacobean society, while cultural materialists (Catherine Belsey, Jonathan Dollimore, Lisa Jardine, Alan Sinfield) frequently prioritise the plays’ contemporary ideological force. Although new historicists would seek to question the canonical superiority of Shakespeare and although cultural materialists would point out that the elevation of Shakespeare as a venerated object has often been politically motivated, neither school would seek to undermine the centrality of the text under discussion. But in his suggestion that Hamlet is merely a theoretical vehicle for a negative assessment of humanist learning, Lewis prises apart an intellectual history from a performance or even a literary one and, in so doing, points us towards a bleak and hollow work of art: Hamlet, as it were, without the Prince.

He is on firmer ground when he critiques, politically, the humanist faith in providence as a strategy “to diminish or deny the function of human agency in making things the way they are” and he writes well on the political opportunism of Claudius and Fortinbras. There is an especially lively chapter on the etiquette of hunting and his scrupulous attention to the language of the play reveals specialist hunting terms that permeate it and underline its predatory obsessions.

But the book’s raison d’être – “Hamlet indicates that [Shakespeare] came to find humanist moral philosophy deficient” – is only one tenuous way of accounting for the inconsistencies, flaws and logical lacunae that pepper the protagonist and the plot. Too frequently, the critical formulations are rebarbative: Fortinbras’ ambition is “a contra-teleological something that is realised by the simple fact of being asserted, and to which a substantial desideratum is incidental”. Hamlet is enabled “to pursue a fantasy of mnemonic erasure”. In places, Lewis sounds dangerously like the bewildered and bewildering philosopher, George, in Tom Stoppard’s play Jumpers: “Unless we define being alive as an affair of ontological passivity – as a condition of significance only because it involves one neither killing oneself nor being dead – it is not at all clear that choosing to live can only be seen as the equivalent of not doing something.” Most bewilderingly, Claudius is “a pretzel in a land of sponge cakes” – with tea or not with tea, that is the question!

Peter J. Smith is reader in Renaissance literature at Nottingham Trent University. He has seen Hamlet more than 40 times and reviewed 20 different productions. He is co-editor (with Nigel Wood) of Hamlet: Theory in Practice (1996) and (with Deborah Cartmell) Much Ado About Nothing: A Critical Reader (forthcoming).

Hamlet and the Vision of Darkness

By Rhodri Lewis

Princeton University Press 392pp, £32.95

ISBN 9780691166841

Published 8 November 2017

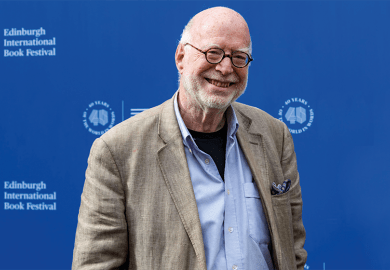

The author

Rhodri Lewis, professor of English literature (and fellow of St Hugh’s College) at the University of Oxford, was born in Haverfordwest, Wales, and had “rather a peripatetic childhood” before going on to read English at Corpus Christi College, Oxford.

Asked about how he has been influenced by Oxford, where he has spent his whole career to date, Lewis responds: “My undergraduate tutor was Val Cunningham, and my recollections of being taught by him are that anything goes, as long as i) it has an argument; ii) the argument is not stupid or borrowed from someone else; iii) the argument does not do violence to the text or texts under discussion. I suppose this has had an impact on me.”

His new book has emerged from Lewis’ long-standing interest in “early modern ideas about cognition, in particular about memory…I’d intended to explore the presence of these ideas in Shakespeare’s work – and perhaps to say something about Shakespeare’s criticisms of them. As I began writing, it became apparent that I was coming back to Hamlet over and over again, and that some of my readings did not sit at all easily with the sorts of things that are generally thought about the play. So, Hamlet it was.”

As for the general state of “Shakespeare studies” today, Lewis believes that “much of the best work on Shakespeare at the moment concentrates on questions of performance history, on questions of reception and cultural appropriation, or – on a different tack – seeks to grind his writings into a lens through which to view the history of x in the late 16th and early 17th centuries…it would be good to see more work treating, and attempting to make sense of, Shakespeare’s poems and plays as artistic wholes. As I found to my own slight surprise in tackling Hamlet, there’s still a lot to say.”

Matthew Reisz

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: More twists than a pretzel

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login